On the upside my old mate Robin Adshead joined forces with me in the Military Picture Library in 1989. Our partnership coincided with the downturn in conventional commercial business after The Rat left me with fourth fifths of bu***r all and I learnt more from Robin about the skills really required for good military photography than at any other point in my career. Wars and other hot spots were our bread and butter, along with a vast amount of stock photography that we shot of the UK and foreign forces, trading shooting and supplying the images to them for later selling them to a wide range of users. I believe that I can lay claim to producing the first full colour brochures for the Army, with 5 Airborne Brigade being to first to benefit. We shot all the material that they wanted, wrote the copy and funded the whole operation with advertising from the defence sector, cementing the symbiotic relationship between them. The Army paid not a penny and we generated some brilliant stock material - a win-win situation. We also helped advise on and set up the first Army Picture Library as it was then called for the Ministry of Defence, but lost out in the bid to actually run it because our prices were deemed to be too high. Curiously the company that won the tender had very little experience running stock libraries but a good business model, enabling them to get the job, even though they later added in the costs of all the things that we had foreseen and budgeted for, making us cheaper in the long run! Robin also encouraged me to start writing, although he was very critical of my efforts and rightly so! We enjoyed a great professional relationship, had numerous fun-packed adventures all around the world, took some momentous photographs and probably drank far too much, but sadly for me his happy remarriage, followed by retirement in Spain beckoned to him. He had earned his retirement and enriched my life, so I was shocked to hear that he only managed a year or so out there before a massive heart attack claimed him.

John Robert Young is the other professional photo-journalist who has made a huge impact on my life. He was first introduced to me by Robin some 25 years ago and has always proved to a brilliant sounding board, a stalwart ally and a real gentle man in the true sense of the word. In comparison to his endeavours in the world of photography I have made but a tiny dent and would consider myself successful if I had accomplished a fraction of his output. From shooting and writing the first in-depth illustrated books on the Royal Marines, the French Foreign Legion and becoming the first westerner to be allowed behind the scenes in the People’s Republic of China’s armed forces, to photographing the great and the good, the rich and the poor and the movers and shakers in society in the second half of the twentieth century he is right up there with the very best of them. After Robin died it was he who carefully read all my draft manuscripts, gently suggesting ways to improve that I would never have thought of. It was he who came to my help on the great Bear Grylls adventure, producing material that has stood the test of time. Whether with a Leica shooting film discretely, or with the latest digital technology he has shown that age is no barrier to learning about and using digital with aplomb. He is probably the best example of a photographer who relies on his eye, rather than on the equipment he owns to get the final result shot to perfection.

From there I became a freelance photographer, with the accent very firmly on the ‘free’ element, as I still had no idea how to really run a business, no matter how good my photographic skills were. However it wasn’t long before I found something closer to home, running the Agfa-Gevaert professional processing line at their lab in Deer Park Road in Wimbledon. At least my Pavelle/Durst skills would be useful and I would be in a position to meet professional photographers, which is exactly what happened. Pretty much every day a photographer rushed in with vast amounts of Agfa Professional reversal film to be processed and we soon got talking. Agfa’s approach to professionals was strange. Having created professional film and installed a professional processing line just for them it refused to acknowledge that they might just want professional service, something that I already understood to be essential. So I would take in film to be processed with the promise to have it ready in 45 minutes or so, when the official line was 24 hours! After a time he asked me if I would leave Agfa and come and work for him. As I was familiar with the work I leapt at the chance and so began five years of fun and games working with Tony Simpson at Audionics. Boy did we work hard for long, long hours shooting advertising work, studio and location stuff, audio-visual presentations, duplicating and so on - all stuff that I was very familiar with from the hospital days - pay attention to details, listen to the brief, give the client what he thinks he or she wants once you have planted the seed in their minds of your way of doing it! I graduated on to Sinar P 5x4 and Hassleblad cameras and Bowens Quad studio flash, allied to tight deadlines. Wonderful. I began to learn about how things actually ran, rather than just about photography. At one time during my time at the hospital had had done a degree-level day release course in professional photography at the Central London Polytechnic in Regent Street, if you can believe such a thing existed. We were all guinea pigs in this pilot course, but very quickly the rough edges started to show. We were taught absolutely nothing about the mechanics of running a business. It was assumed that because we were going to be great photographers we could expect clients to beat paths to our doors. Nobody ever mentioned ways to let those potential clients know that we existed! If the degree course had included 50% business studies it would have kept all 28 or so of us on it to the end, but it didn’t and of the half dozen or so of us who lasted 18 months we were the only ones, so far as I’m aware, to ever continue in a photographic career. It was a complete waste of time. Even the photographic side was really pointless, lighting manikin heads for example, rather than learning something of everyday practical value like how to balance daylight and flash when shooting on location. My view, even today, is that you can either see a photograph in your mind’s eye or you cant’t. If you can’t then you never will and that’s then end of it, but if you can you can only get better through practice and more practice. In those days of course practice cost money - lots of money as film was pretty damn expensive to buy and process - and that had to be done to get any results. Today with digital it can be expensive to buy the initial kit you need, that’s true, but actually practising your craft is effectively free of direct costs which makes it a beginner’s delight.

All through the 70s and 80s I was honing my photographic skills, as well as doing more and more work with the armed forces both at home and abroad, with Her Majesty’s Government picking up the tab as they did in those golden days. I can’t say that my business skills improved much, but when you find that you are one of only a handful of photographers who specialise in defence-related photography more and more clients beat a path to your door and you find that you can pretty much charge what you want. The big problem has always been that I have found it easier to spend money than to make it! I was never a ‘gear-oholic’, constantly buying the latest kit or swapping from one brand of camera to another as many appear to do today. I could never see the point, nor could most professionals that I knew. Certainly none but the most well heeled, or those working in big corporations, could actually afford to change systems, let alone find time to re-learn everything. That’s why I have stuck with Nikon as my sole 35mm/digital camera system throughout my career. It may be the best - or it may not be the best - who knows, but I’ve invested a huge amount of money over the years, understand exactly how it works, have never felt the need to change it if it ain’t broke, so it’s the best for me. I’ve tried Olympus OM1 and Canon F1 systems and hated the ergonomics of both. I’ve tried Canon digital and hated both the ergonomics and the results. I’ve tried Fuij digital and loved the results but hated the ergonomics. So why change?

However, I could also see that I didn’t want to spend my whole life doing this - it was a step in my learning ladder. Alongside my work there every spare day or holiday was spent photographing the armed forces. This wasn’t so hard then as it might be today. There were more open days on ranges and things and security was never an issue, so I ingratiated myself with units and was asked to cover exercises and such. I returned those favours by supplying prints to the units by way of thanks. Slowly my contacts broadened and I found myself starting to be invited to cover exercises or press days, across all three services. And just by being in the right place at the right time I got to do things that had many of my friends green with envy! I had a flight in an RAF English Electric Lightning T.5 out of Binbrook in ’72, out with other Lightning F.6s from No 23 Squadron high over the North Sea. I’ve never flown so fast or so high since I don’t think! A few years later I got a ride in a Spitfire Tr MkIX, just released from duties with the Irish Air Corps and painted in an interesting shade of yellow. Still, beating up Middle Wallop airfield at 300 knots at zero feet in a Spitfire, yellow or not, was an experience that I’ll never forget. That was only because I was there shooting something completely different for the Army and had seen the Spit come in to land, so wandered across with a slack-jawed look and innocently asked the pilot, lounging by the aircraft, if there was any chance of a quick flight. He scanned his watch, looked at the sky and said that if we made it a quick one it would be OK!

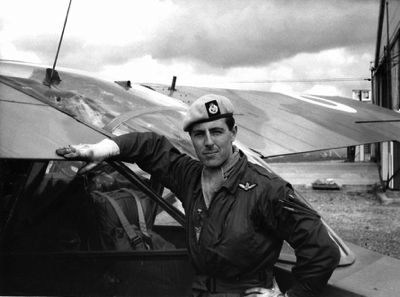

It was around that time that I first met someone who was to have a major influence on my photographic career - one of only a few who have made such a difference to my photographic skills and my approach. Back in 1971 Maj Robin Adshead had just left the army after serving as a Gurkha officer in 6th (Queen Elizabeth’s Own) Gurkha Rifles (6 GR), having fought during the Emergency from 1954-1960 in the jungles of Malaya (as Malaysia was then known), Confrontation from 1962-66 in the jungles of Borneo and raised the first Gurkha Air Platoon flying Sioux helicopters then transferring to the Army Air Corps, before finally succumbing to the defence cuts in the early 70s. When I first met him, swathed in Leicaflex cameras with impossibly long lenses fitted and all the ‘right’ gear, I was transfixed. After talking at length with him I realised that this was who I wanted to be - the military photo-journalist par excellance - the doyen of defence photographers. He was the author of a number of books, including ‘Gurkha - A Legendary Soldier’ and features editor of Battle magazine, the leading defence-related monthly magazine produced by the Ian Allan publishing empire. Nineteen years older than me, he took me under his wing and nurtured and guided me through my first tentative years in an unfamiliar environment. Our paths often crossed whilst covering events in the 70s and 80s although we were, in effect, competing for the same market, but that never stopped him from encouraging me. It was only at the end of the 1980s that we finally joined forces in the Military Picture Library, a company that I had formed way back in 1971, initially to get me in to military circles, rather than as a marketing tool. That would come later.

It was at this stage that the two families met, with my father joining DCS after demob from the army, meeting my mother and soon after producing me! DCS soon evolved into the Directorate of Overseas Surveys (DOS), where my father worked until his retirement. Subsequently DOS was subsumed into the Ordnance Survey. My childhood was spent surrounded by air photographs and maps and I soon became an expert map reader. The house was also full of rifles, booby traps, grenades, ammunition, bits of uniform and shelf upon shelf of military books that held a fascination for an army-mad youngster. I was convinced that I wanted to join the army when I grew up but it was only after I was given my first camera, a Kodak Box Brownie that I still have, that a seed of unease with my goal was sown. At school I was in the army section of our Combined Cadet Force and Field Marshal Montgomery of Alamein was our school governor. He visited twice, maybe three times, whilst I was there and on at least two occasions sat down to lunch ‘with the boys’ to sound them out. Each time I sat right next to him and chatted, but luckily I didn’t know until years later what havoc my father must have caused him in his great desert campaigns by blowing things up! I loved every minute of cadets, particularly the shooting and it was during a day on the ranges at Bisley that my interest in photography was heightened. A friend showed me his new camera, a Practica I seem to remember. Initially I was not overly impressed, even with actually being able to look through the taking lens, until he unscrewed the lens and attached a 135mm one. I remember being absolutely knocked for six! I suddenly saw the world in a whole new light. It was as if lightning had struck me, causing a blinding revelation. From that moment on my interest in photography was all consuming.

In the first instance I had never thought much about telling the world anything about me. What could a relatively unknown photographer say that would be of any interest? However my children, ever mindful of the fact that I could pop my clogs at any time during this COVID pandemic and leave them with unanswered questions, along with some friends who said, “Well you seem to have an eventful life, why don’t you tell others about it?”, has spurred me to do something about matters before it’s too late. I’ve been told that I must produce an autobiography, probably more for my children to cash in on the proceeds, poor fools, than for any genuine interest in what I’ve done. Still time will tell. If you make it to the end of this scribble I consider that you are made of stern stuff!

Firstly, a bit of background to set the scene. I was spawned from a background of military families mixed with photographers and artists; my paternal grandfather served in the Second South African (Boer) War in a privately raised cavalry regiment, Paget’s Horse, Imperial Yeomanry, rising to CSM before wounds and illness saw him repatriated. Moving, or returning to Argentina - we are not sure which - he forged a career in the country before rallying to the call of the Old Country in 1914 and returning to join another special war-raised unit for crown colonies’ volunteers, 2nd King Edward’s Horse. Fighting through the war and being wounded once, he was commissioned on his return to England to get married, whence he was posted with his unit and new bride to Dublin, part of the Irish Free State in those days, where my father was born. A grateful government then paid for my grandparents and their son, my father, to move back to Argentina where they lived until 1936 before coming back to England to build a house by the sea at Sandbanks in Dorset, now part of Millionaires Row. Indeed the house is one of the very few still standing today that have not been modernised or knocked down to be replaced with hideous glass and concrete monstrosities. Not long after they moved in, my grandfather succumbed to his war wounds, the house was sold and then war appeared on the horizon. My dad immediately volunteered for service but because he was in a protected job, helping administer the workers constructing St Eval Airfield in Cornwall, he was not called up until early 1940. Against his wishes he went into the Royal Corps of Signals, which is what probably saved him as his first choice was the infantry. Completing his training his whole course boarded a troop ship for an undisclosed destination. He had two days shore leave in Durban, South Africa, before finding himself aboard his ship, but minus all the other ‘scalies’ from his course. Sadly, they all went direct to Singapore, capture and eventual death in Japanese captivity while he went to HQ 8th Army Group in North Africa.

While still working at the hospital I started to invest in better equipment. Turning up at one’s first military photo-shoot armed only with a Zenith B and a Prinzflex TTL and two crappy lenses in the company of the elite, almost exclusively armed with Nikons save for Robin with his Leicaflexes, was too disheartening. They were also far too unreliable to do what I was asking of them. However, once again Lady Luck was looking over my shoulder. Every day on arrival at London Bridge Station I had to pass Vic Odden’s London Bridge Camera Centre and that became a magnet for me. In its day it attracted many professional photographers who didn’t want to make the longer trip to Pelling & Cross or Wallace Heaton to swap their used kit for new, so I soon picked up a couple of Nikon F bodies, an F-36 Electric Motor Drive and a range of used NIKKOR lenses, although I confess that I did have a false start. Like many aspiring young photographers I couldn’t really afford much, certainly for genuine NIKKOR lenses, after making a huge commitment to Nikon bodies, so I chose the next best thing - so I thought. I bought two much cheaper independent brand lenses. Previously I had owned a Wallace Heaton-branded 240mm f/4.5 Zodel Pentax screw mount lens (who remembers them?) and was as impressed as any wet behind the ears youngster could be of its qualities. Of course I had never really pushed that lens to its limits, so when I bought a Vivitar 28mm and a Hanimex 400mm lens I expected pure magic. Neither lived up to expectations mechanically. Optically they weren’t too bad at all, but that optical integrity relied on the mechanical quality to keep the lenses working while suffering the normal sort of abuse that professionals dish out to their kit. This was brought home to me in a salutary fashion when I lent both lenses to a good friend to take on safari to Kenya. After a mere two weeks they were returned to me absolutely destroyed. The oh so smooth focussing of new lenses gave the impression of fine engineering, but the reality was that the engineering was rough and the smoothness was created by the large dollops of grease that coated the roughly cut threads! Fine Kenyan dust had impregnated the threads of both lenses, rendering them completely f***ed, to use the technical expression. I learnt a valuable lesson very quickly and, thankfully, without too much financial loss - buy cheap, buy twice. It is better to save up for what you want rather than settle for second best, and that is a principle that I have stuck with ever since. I’ve never bought a non-Nikon lens since that day nor have I ever had cause to regret waiting to buy the right lens.

Because of my long hours looking through Vic Odden’s windows and passing wads of cash over his counter I began to draw the attention of the late great Vic Odden himself and after a few years he asked if I would be interested in coming to work for him, setting up and running a commercial studio. The rewards were very attractive, with a good salary being offered as well as discounts on new equipment and the ability to buy secondhand kit at the price that he bought it for. That fact that I knew absolutely nothing about the actual mechanics of running a business never entered my head! After all, I was a professional photographer - surely that’s all that was needed? Well, the long and short of it was that it failed for two reasons. The first was that Vic’s heart was not really and truly into this side of the business nor was he very well at this time either, whilst the second reason was that I had no idea at all how to market the studio or attract clients. Thankfully I enjoyed a salary despite my abject failings and rapidly converted that into Nikons, so he got all my money back again! I forget how long I spent there, although it was certainly long enough to get a Reflex-NIKKOR 500mm f/5, a Fisheye-NIKKOR 8mm f/8 and a couple of Remopaks for my motor drives. Sadly, the constant cash crises of youth saw all those rarities converted into newer Nikons - something that I now bitterly regret.

About Me

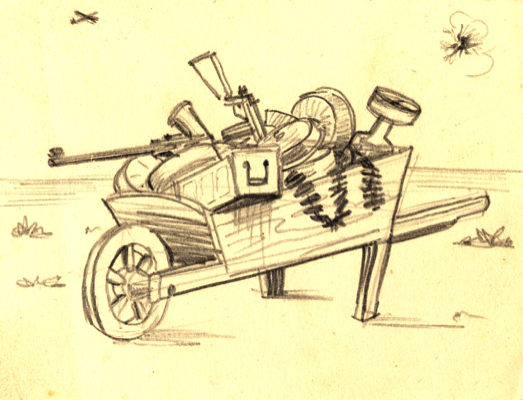

Life for him, a 21 year old at war, was one big adventure as the conflict ebbed and flowed first west, then retreating east before the big push westwards after the second Battle of Alamein. As a kid in Argentina, his father had given him 10lbs of gunpowder on his 10th birthday with the advice, “Make your own arrangements, but don’t kill yourself”. The deserts of Africa gave him ample opportunity to add to his explosive collection, first with the odd Luger pistol or German stick grenade but processing up to a sizeable collection of weapons and explosives. A sketch from the period by one of his mates shows his ‘toys’ in a wheelbarrow! His posting with Montgomery at HQ 8th Army afforded him plenty of storage space but boredom and youthful foolishness soon gripped him and his collection overflowed his signals caravan and migrated to any available storage space. He also took to placing detonators in the doors of his caravan, with their cracks as they exploded delighting all his mates. Inevitably there was a downside to all his tomfoolery and on the eve of the first Battle of Alamein a detonator sparked off a sympathetic detonation of a large part of his collection, destroying the signals caravan and putting him into a base hospital in Cairo. Following his recovery and possibly a spell in the detention centre for naughty boys he was recalled to his post, so he must have been an above average signaller. Supporting this he was then seconded to the fledgling Long Range Desert Group and later the SAS before returning to HQ 8th Army Group for the historical reversal in British desert war fortunes at the second Battle of Alamein.

He then started to reassemble his ‘big boys toys’ as he moved westwards through Africa, into Sicily, on to the landings at Salerno in Italy, before fighting up through Italy and into Germany to stay on as part of the army of occupation. In late 1946 he flew back to Britain in a Lancaster after being away, without a single home leave, for almost six years. Many of his ‘toys’ were later given to me to play with, with his father’s advice, “Make your own arrangements, but don’t kill yourself”, added for emphasis! I think for him, like many of his generation, the war years represented the most exciting years of his life, coming through pretty much unscathed apart from self-inflicted wounds caused by his penchant for explosives.

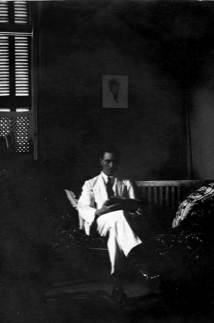

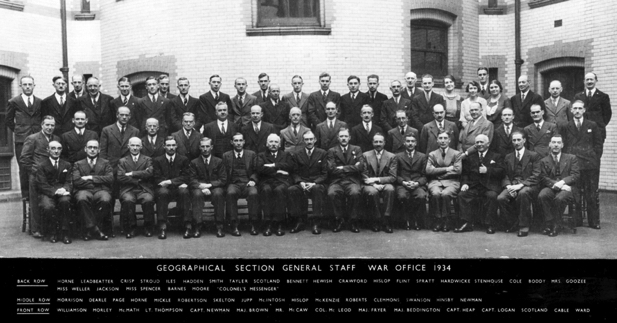

My maternal grandfather came from a family that had many artists amongst their number as well as a cousin who had photographed the Russo-Japanese War in stereo and in colour, way back in 1904-5, long before colour film was readily available on the domestic markets. Sadly his mother threw all the negatives away when he later served in France in the Great War. My grandfather also took his camera to France in WW1 where he served with the Royal Engineers doing surveying and cartography, working with Geographical Section General Staff (GSGS), later to also be known as MI4. At some point, either during or just after the war, he met TE Lawrence who also worked in GSGS, and he later produced all the maps for the 1940 edition of ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’. Immediately following the end of the war he worked for the War Office in GSGS and was seconded to survey Sudan for the Sudan Government Survey until 1924 before returning home to marry and raise a family. In 1928 he invented the Photonymograph - the groundbreaking forerunner of the phototypesetter that revolutionised type and printing right up until the introduction of computer generated type. For this he was awarded the princely sum of £100 by a grateful Government. That said, one could buy a house for £100 in 1928 - which he did - so it wasn’t as meagre as it sounds. He worked for the War Office right through WW2 with GSGS, preparing all the mapping for D-Day amongst other things and after the war vied for the post as director of the newly formed Directorate of Colonial Surveys (DCS). That he came close is evinced by the fact that my mother was employee number one! Sadly he was considered too old for the post and his long-time friend and colleague Brig Martin Hotine got the job.

Ernest McIntosh, Khartoum 1923

Geographcal Section, General Staff, War Office 1934

Ernest McIntosh, standing 9th from left

My mum Audrey, DCS 1949

Brig Martin Hotine (2nd from left), my dad Bill and the Duke of Edinburgh operating a Multiplexer, DCS 1950

However, I still harboured my dream of joining the army and left school with that intent, but a family friend said that I could easily earn more money from photography than I was ever likely to do in the army. So I made my first big mistake very early on in life!

I must confess that, unlike almost all my friends, I have never actually had a plan in my working life - not one. I’ve just sort of bumbled along, getting knocked down a few times, but more often than not succeeding by being in the right place at the right time and then proving that I could come up with the goods - being professional in fact.

I started out determining to learn the basic underlying skills of photography - film processing. I was a hopeless photographer, I really was, and looking at some of the few shots saved from the late 1960s and early 1970s I’m amazed that I ever made a successful living from it. I joined Pavelle UK as a colour negative processing technician. Pavelle, soon to be bought by Italian giant Durst, manufactured dip and dunk processing machines and alongside the production line ran a processing laboratory where they were tested by taking in D&P work from the local chemists in and around Epsom. I learned quickly, but soon became disillusioned when I’d go into the lab on a Monday morning to find just pipes hanging from the wall as, overnight, a processing machine had been sold, dismantled and shipped to its new owner, leaving me and my colleagues with no way of processing that day’s intake!

In those days, in the early 1970s, pretty much every company of a reasonable size employed an in-house photographer or had an in-house studio with all the key facilities, so the job market place was simply vast. Getting a job was certainly not the hardship that it is today. I recall that I only applied for two jobs; one as a studio assistant with Freemans, the mail order catalogue company, and one as a photographic assistant with the photographic section at the London Hospital Medical College. Up to that point I had never given a thought to the existence of medical photographers, but anyway I went up to Whitechapel for an interview, not knowing what to expect. What I discovered was a small unit offering a huge range of photographic services across the college and the hospital. They did the typical medical type photography, although with a difference as the unit worked in the Department of Pathology, meaning that they never, ever saw a living body! I don’t know how many people applied for the job - I never did find out - but the boss, Dick Hammond, only lived a couple of miles from me and probably thought that a one hour train journey every day would be marginally less boring if it was shared. I certainly cannot have been employed for my photographic skills.

However my time there was neither wasted, nor dull. We may have only been a three person unit but the scope of work and the wide range of skills used meant that I covered everything from precise macro and micro photographic skills, grip and grin shots as we called them for PR purposes, advertising work for new products, working in post mortem rooms (similar to operating theatres but with no hope of recovery!), processing and printing and so on, covering almost the entire gamut of photography. We used ½ and ¼ plate cameras, often with glass plates rather than film, roll film using Rolleiflexes I think and 35mm using Exacta cameras initially, mainly because the Bursar had been a prisoner of war of the Japanese and refused to buy any Japanese product unless there was nothing else to match it! Soon after I joined the Exactas gave way to Minolta SRT101s, much to my delight, as I have always hated the ergonomics of Exactas, however good the results might be. For all 35mm and roll film printing - all black and white in those days - we used a superb Leitz Focomat IIC which I still class as one of the best enlargers ever produced. For the larger stuff we used an ancient Kodak whole plate enlarger that seemed enormous, taking up a huge space in one of our three darkrooms. And the volume of prints that we - well I produced, being the junior - was also astonishing. I recall producing 1000 identical hand dodged and shaded black and white prints a day from one negative on occasion. That certainly encouraged me to learn to print quickly and precisely. Remember that was also in the days before multi-contrast papers, so we’d have massive boxes of different grade papers to suit all types of negative.

An early 'selfie' aged 19, taken on a Nikon F with F-36 Electric Motor Drive and Fisheye-NIKKOR 8mm f/8

RAF English Electric Lightning T.5 over the North Sea with Lightning F.6 ahead, 1972

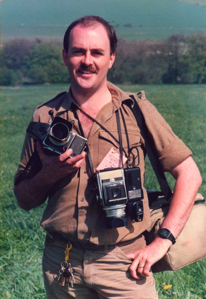

Capt Robin Adshead, OC 6th Bn QEO Gurkha Rifles Air Platoon, at Kluang, South Johore, Malaya 1967

Self, Robin Adshead and Capt Robin Hood, 17th/21st Lancers, on Salisbury Plain 1992

From top left - self perched precariously on a Quad bike with 160 Provost Company, 5 Airborne Brigade, at Keevil in 1994, sitting on the ramp of an RAF Hercules low over Otterburn in 1990, using Hasselblads on Salisbury Plain with the US 82nd Airborne Division (All American) in 1987 and with 29 Commando Regiment, Royal Artillery in the Omani desert in 2001.

The 1980s were quite traumatic years for me in many ways. I was made redundant from my dream job after a change of location for the studio failed to have the existing client base follow us. I learned about the hard economics of the business world, with no regrets I must add. As an employee I became economically unsustainable and had to go. It was the worst thing that had ever happened to me and yet the best; it forced me to go out to become properly self-employed. For those who have never worked for themselves or perhaps never want to be anything but an employee, being self-employed is seen as the height of luxury. You can, so they imagine, do what you want, when you want, for however much you want! If only that were true. The most succinct way I have heard the difference between being an employee and being self-employed described is this; being an employee means knowing that your mortgage will always be paid, that your table will always have food on it and that your two week holiday to Spain every year will be fine, but you know that the lovely country cottage that you secretly yearn for, or the Ferrari that you dream about will never, ever be within your grasp. The reverse is true for the self-employed; you never know if you can find the next mortgage payment or if you can put food on the table from week to week or if you can take your family for a single week on holiday, but you know that the country cottage or the Ferrari is always just one great job away, never completely unattainable. That’s the simple choice between the two forms of employment.

I also discovered the hell of working with a partner that I trusted, only to find that when I left the country to go on holiday with my very pregnant wife he wound up the partnership and took everything. We had formed a partnership working out of my drive-in studio in the latter half of the 1980s, sharing the photography (as much as his pride would allow) but with him and his partner doing all the ‘nasty running the business stuff’ that I hated so much and for which I was so thankful. So to arrive back in the country and be accused of taking more than my fair share from a business that I was actually unable to withdraw money from without their approval was bitter shock! In the days before web sites and email addresses allowed the relatively free and easy transfer of businesses, a company’s phone number was one of its main assets and marketing tools and he took it. My wife told me not to trust him and I ignored her, so we both paid the price of my folly.

Tony Simpson at his 60th birthday dinner

Self with trusty Nikons, Bovington Camp, 1982

Robin Adshead with his beloved Leicas, Galloway Forest, 1992

John Robert Young with his beloved violin, 2020

The older I get the less criticism affects me. Back in the good old, bad old days I often felt that everyone was out to attack us, overlooking the fact that it was just how good cut-throat business performs. I have always prided myself on trying to do the very best I can for a client and ended up with lifelong friends as a result. That’s worth more to me than cut-throat business techniques and, I suggest, should be a lesson for all professionals in any field. There is more to life than money, although I confess that it’s hard to say that to someone just starting at the bottom of the pile.

The massive shake up of the stock library field by the giants such as Getty and Corbis in the early part of this century did nothing for independent stock libraries like mine, as clients found that they could often get much of what they needed at a fraction of the cost that we charged. Bear in mind that any stock library that sells contributor’s images, rather than the owner’s, has agreements in place that typically allow a 50/50 split on royalties. When the front cover of a book could go for £600 perhaps or the front page of a newspaper for double that for the right shot there were rewards aplenty for both parties. Competition from the giants meant that they might charge only a handful of dollars for a similar shot, and only pay contributors 5-10% of royalties the writing was clearly on the wall for small independents. That downturn coincided with my move from Aldershot to the wilds of Somerset in an effort to escape the increasingly stressful rat race, and whilst worrying at the time it actually turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Competing with companies that have millions to throw at a library became impossible, so I didn’t even try! If someone wanted to purchase the rights to specialist material that we held then that was fine, but I never pushed it after the move. Life is too short to die of stress. So the stock library died a natural death and specialist commercial work, very often in the defence sector, took over. I started doing more design and print and web site construction too, taking the sting out of the change. I guess that I was lucky too that I didn’t have a mortgage to service, which as always one of the biggest chains round the neck of the self-employed.

I also finally got to be employed by Her Majesty too! Working first as a Public Relations Officer for an Army Cadets county, then climbing to Master Photographer for the whole South West of the UK, even at the low rate of remuneration by commercial standards, led to contracts to cover more of the same at a national level, doing what I love and am good at. But would I want to be twenty years younger? No, not in the current climate!